Compared to that of other instruments, the guitar’s repertory consists predominantly of short pieces. While pianists, string and wind players regularly tackle lengthy masterworks, guitarists usually program seven, eight or more works in a single night. Furthermore, our repertory appears lighter, or less ambitious, than that of other instruments. We certainly wish that composers such as Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms and others would have written monumental works for guitar like those they wrote for piano or diverse ensembles.

19th-century solo guitar works seldom passed the fifteen-minute mark (such as some sonatas by Sor, Matiegka, Gragnani and Diabelli, or Giuliani’s Rossinianas). Single works or separate movements rarely broke the eight- or nine-minute mark, and many of these did so with the help of a slow introduction or were comprised of sets of variations. During that time, sonatas for piano or chamber ensembles grew into the thirty-plus minutes, with single movements comfortably reaching ten minutes or more. This is no criticism of our guitar composers, who were quite capable of conceiving and balancing longer music (the Italians wrote guitar concertos and various ensemble works, Matiegka wrote long chamber works with guitar, Sor wrote operas, ballets, a violin concerto, and more.)

Why didn’t guitar composers write ambitious works of at least twenty minutes like those common to other instruments? And why are such works still rare throughout the 20th and 21st centuries? Among the various reasons that might come to mind, one that is simple, but somehow overt and hardly given the consideration it deserves, lies on the very nature of our instrument. Since the guitar is a smaller instrument in terms of range, dynamic, sustain, and polyphonic possibilities, guitar works are shorter. Reflecting on this seemingly simplistic reason can be quite revealing.

The discursive nature of Western music, which reigned well into the 20th century, placed the length and significance of a work in close relation to the instrument’s technical and sonic possibilities. This is a rather intuitive concept; the ways of developing a music idea in interesting ways, or of creating contrasts with it, narrow as the instrument of choice reduces the pitch and dynamic ranges, its sustain shortens and the polyphonic/counterpoint writing becomes more intricate. Then, the natural arches of the discourse–the unfolding of drama and its resolution, the buildup of tension and its release—must be shorter. And a proficient composer would know how much to stretch the ideas, and abide by the instrument’s possibilities.

On the other hand, more possibilities lured composers to plan longer and more complex works. As the piano developed mechanically during the 19th century, its works became larger. The century ended with enormous symphonic works such as those by Mahler, Bruckner and Strauss, which depended on huge instrumental bodies, capable of the widest ranges of pitch, dynamics and colors. In this way, 19th-century aesthetics played against the guitar; in the century of program music and unbound emotions, limited resources hindered the narrative of grandiose stories. Many times bigger meant better.

Let’s consider the following passage of Beethoven’s Sonata 23 in F minor, “Appassionata” (mm. 123 to 135).

It consists of an E°7 chord that becomes a dominant C7, in preparation for the recapitulation on F minor. Just two chords–but the passage takes approximately thirty seconds! First, the diminished-7th chord is arpeggiated throughout much of the piano register, and then, at fortissimo dynamics and with much intensity accumulated, six more bars are needed to diminish to pianissimo, release the tension, and arrive to a restrained recapitulation. Similar procedures (covering the complete pitch register and diminishing from ff to pp) would take substantially less time on guitar–at least if one were to avoid redundancy. This is just one particular example, but I hope it illustrates the bigger point. And this was Beethoven; the section is “long” but hardly disproportionate or redundant. It is in proportion to everything else in the work.

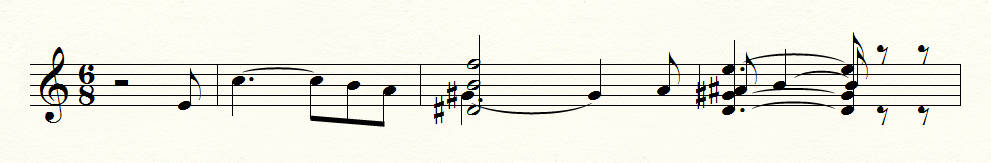

Then, there is the instruments’ “technicality,” which affects the body language of its performer, which in turn plays a significant role in a musical narrative (though seldom considered). Take the serene and expansive openings of Schubert’s piano sonatas D.894 or D.960 (of which just the first movements approximate the 20-minute mark!). A pianist can play these openings with minimal body motions, delicately breezing through the chords, visually matching the pianissimos, and inviting the audience into a meditative atmosphere. After such openings, a work has plenty of time to develop toward a more technically-involved one. A guitarist, playing a similar texture of continuous chords, would most likely transmit more intensity to the audience’s eyes and ears. Think of how tackling it is, for example, the middle section of Regondi’s Reverie, Op. 19, of which the beginning is shown:

In this example, the lyricism should prevail, with a rather playful and romantic mood that should hardly include any drama or signs of struggle. Yet the audiences’ eyes will see a good deal of motions of the left hand, and the performer has to be quite proficient in order to deliver a lyrical tenor line while avoiding chopped chords, sudden position shifts, heavy breathing, or other audible cues to the passage’s exigent technical demands.

In closing, and far from intending to belittle the guitar, my intention is for us, guitar performers, arrangers and composers, to reflect on the unique nature of our instrument. It might help with planning the composition of a work, helping us to better know what to ask of the guitar and what to expect from it. It might give us a sense of what pieces can be successfully transcribed to the guitar or not. It might help with the planning of our performances, helping the public to understand the music. As practice, listen to piano sonata movements, or other types of lengthy movements for diverse ensembles. Compared to a similar guitar movement, how many more elements, themes or general ideas do they have? How much more ‘inspiration’? And how much of the length difference is due to similar processes taking longer to unfold? Can you imagine how these works would sound on guitar?

I hope that thinking about the aforementioned points becomes enlightening in some way!