Archive for year: 2015

Tempo do Brasil reviewed on Soundboard

Nice review of Marc Regnier’s album “Tempo do Brasil” on Soundboard Vol. 41 No. 2. “This is a thoroughly delightful disc. There is great playing from Marc Regnier and a first-rate group of collaborators, infectious music, and good programming. Get it… Regnier and Uruguayan guitarist Marco Sartor make a powerful and well-matched duo… The excelent liner notes are by Mr. Sartor.”

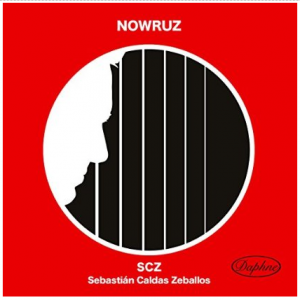

Thought Spots: Giulio Regondi’s “Reverie, Op.19”

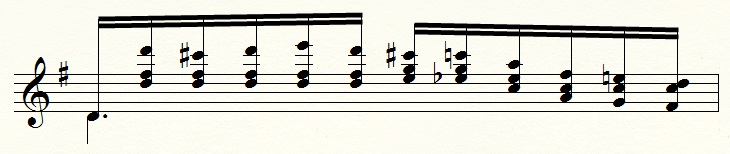

This passage in Giulio Regondi’s Reverie, Op.19 is a sort of music-analysis puzzle:

Giulio Regondi: Reverie Op.19, mm. 88-90

There must be a misprint somewhere in the group marked with X. As it is printed, it hardly constitutes a valid harmonic progression in the practice of the time. We can have certainty that the last chord of the group is D7, which serves as dominant to the G-major harmony in the next bar. Then, we can safely guess that the C’s of the previous two chords are also natural (a D7 – C – D7 progression). These two chords could work with C# as well (F#m-A7-D7 progression), but I think it is more likely that they have C’s, and virtually every guitarist plays C’s. The C# alternative comes from the C# in the first half of the bar; at some point the pitch C# has to transition to C within the bar, but we cannot say exactly when, since the natural sign is missing.

The first three chords of the group are the puzzling ones. The first chord, C#-minor, can work as such (notice that I assume the top note to be C#, for there was a C# in the same bar). The second chord, however, is not a valid one here. It has the structure of a dominant-seventh chord, but it is neither spelled nor resolves as such. The spelling is that of an augmented-sixth chord, but then it should resolve to a D or G chord, which again is not the case. Furthermore, the chord leaps to an A-minor triad, which makes the passage even more clashing as it is written. Considering the C# variable, this third triad could be A-major, and this possibility will be briefly considered below. Again, I have only heard C and not C# for that and the successive triads.

So, there is a misprint somewhere. It can be an accidental missing or misplaced, a note misplaced, or a combination of them. So how do we “correct” this group?

Let’s consider some possibilities. Perhaps the sharp and natural signs of the G’s are misplaced and actually belong to the C’s. There are a few points that support this: (1) the C#-C descent must happen at some point and it is not marked; (2) as written, the first and second triads repeat the C#, which is strange within a descending group, especially considering that this descending gesture occurs in other parts of the work and never features repeating melodic notes; (3) the G#-G motion of the middle voice is actually awkward in the context of the other voices. So perhaps what Regondi intended is:

This progression works (can be an acceptable harmonic progression within the style), but the parallel C- and A-minor triads do not sound too satisfactory, at least to my ears. Many guitarists play a similar version, with the original motion of G# to G, which renders three parallel minor triads:

Though certainly left-hand-friendly, it is doubtful that Regondi intended such progression.

Many guitarists–I might dare say most–play a progression that sounds well, but looks completely different than the printed edition. (This is the version David Russell plays and that is probably why it became the most popular one):

This version sounds nicely, but changes many things. Since it only needs a natural sign on the C, it assumes that all other accidentals on the score are misprints. It also changes the notes of the second chord. Therefore, we can hardly consider it to be Regondi’s intended progression. Truth is, if we take the liberty to remove or change so many signs from the score, then we can build other versions, some of which sound well and appear more similar to the original. For example:

Or one with accidentals that resemble a bit more those in the original:

There are a few other options that would work. For example, in both of these cases, the first chord can have A instead of G (A-minor and A-diminished triads respectively), and/or the second chord can substitute the G# for F.

In the last three examples, we have considered the possibility that the first chord of the group already contains C instead of C#. We should note that this means that the other two notes of the chord cannot be E and G# as printed. They form an augmented triad that is unprepared and hardly justified by the voice-leading or as some sort of passing sonority. We can alternatively assume that both first and third chords have C#, and then a few possibilities open for the second chord, albeit hardly resembling the original. This one, for example, works nicely and foreshadows the sequences that start at measure 97:

But we might have delved into too many changes; let’s consider the original group again, and try to move from C# to C in the first two chords. In “Giulio Regondi: The Complete Works for Guitar” (Monaco, Chanterelle ECH415), Simon Wynberg mentions a piano transcription by Frederic Alquen, published in 1871, that has this version:

Again, I am not convinced by the sonority of the two neighbor minor chords. (Nothing wrong with neighbor minor chords–Regondi includes them, for example in measure 101–but for this particular progression I think he would have written something more elegant.) However, this version is particularly interesting in that it maintains the Eb throughout the group. Furthermore, we could assign it some sort of historical validity, for Alquen might have based it on a performance he heard at the time. With all this in mind, the following two versions have the same “amount” of accidentals as the original and create tasteful harmonic progressions:

or:

Now let us go back to the original group. What if the natural sign of the third triad alters not the E, but is actually a courtesy sign for the C? A few points would support this option: First, alterations on the same name note across different registers (same “pitch class”) are specified for each of the registers. Look at measure 88 in the first example. The middle and high C#’s both have sharp signs; we should then expect that both the high- and middle-register C’s in the next bar carry natural signs. Second, this option maintains the Eb throughout the group, like Alquen’s version. Third, it looks closer to the printed score than most others. Voilà:

Although this is the version I play and personally favor, my aim is not to argue for a correct, definite version. By presenting all of these options, I simply hope to help guitarists avoid versions that do not work and/or do not make justice to Regondi’s musical language and ingenuity. Have fun analyzing and experimenting with these and other alternatives, and let me know your thoughts!

Thought Spots: Joaquín Rodrigo’s “Sonata Giocosa”

There is a passage in the third movement of Joaquín Rodrigo’s Sonata Giocosa that I have always found interesting:

Joaquín Rodrigo: Sonata Giocosa, mvt. III, mm. 137-144

The passage, like the rest of the work, is tonal. Each beamed group of eighths suggests a chord; the first and last note of each group belong to the chord, and the second note of each group is an appoggiatura to the last. These chords, in turn, form a clear, tonal harmonic progression. Clear as it is on paper, it is however difficult to understand these harmonies when listening to the work. The reason is that the appoggiaturas rarely sound as such. Displaced at a higher register, those notes acquire a prominent role and render the harmony ambiguous. Furthermore, their prominence is usually strengthened by interpretations that accent them and/or let them ring over their resolution notes, which blur their melodic function. Since the piece moves quickly, there is barely enough time to process the appoggiatura-resolution pairs, which are rather processed as some sort of false relations. And thus the work sounds suddenly “atonal” for a few seconds. I would imagine this is particularly the case for first-time, untrained listeners.

We should then downplay the appoggiaturas (they will sound clearly regardless, since they appear by themselves on a high register), and of course damp them toward the last note of each group. I would also consider two alternate voicing options: (1) to move the last note of each group an octave higher (Figure 2) or (2) invert each group, so as to retain the shape and “gesture” of each group but feature the appoggiaturas on the lower octave, where they are less prominent (Figure 3). I encourage you to try these; even if you keep the original version in performances, they might bring you a new insight for the passage.

Figure 2

Figure 3

On a related note, this passage has led me to write an article about the dissonances in Rodrigo’s guitar music. It will be published in the upcoming Soundboard, Vol. 41, No. 3.

Thought Spots: J.S.Bach’s “Sonata BWV 1001”

When transcribing music for bowed instruments to the guitar, bowing indications can give us valuable insight into how the music should be articulated. However, they can also mislead us if we assume they are invariably included for musical purposes. Sometimes they clarify technical aspects of bowing, which for us guitarists means that we should not read them necessarily as guitar articulations. Let me explain with the following example from the Fugue of Violin Sonata BWV 1001 by J.S.Bach.

J.S.Bach: Violin Sonata BWV 1001, Fugue, mm. 29-32

Bow indications are scarce in this Fugue (and others), for the polyphonic texture requires a specific, mostly unambiguous way of bowing, and the sixteenth-note lines of the episodes are to be played detached. A different case is, for example, the Adagio, where chains of ornamental single notes can be articulated in many different ways. When bowings are included in the Fugue, it is likely because performers would be musically inclined to group the notes differently.

Such is the case in this example. These bowings are technical in nature, to prevent the passage from sounding “choppy” by changing bow directions at every eighth note. They are included because they are musically counter-intuitive: the single eighth notes anticipate the next chord, instead of deriving from the previous one. Many guitarists interpret them as “appoggiaturas,” playing strong chords that “resolve” to the single eighth notes, which come slurred and softer. (Many violin players also follow this interpretation, aiming to achieve a “sigh” effect, which some treatises considered as actually implied in the slur markings.) We should notice that the single notes are anticipations instead of resolutions. They belong to the next chord’s harmony instead of resolving a dissonance from the previous chord. Then, grouped in pairs of single eighths/chords, it becomes clear that these are iterations of the repeated notes of the Fugue’s theme.

It is interesting to notice that the slurred, “sigh” interpretation does agree with the dynamic intent, for the single anticipating eighths should be softer than the chords, just in the same way that the repeated notes of the theme should be played crescendo. In the guitar, however, we can also be coherent with the detached articulation of the theme simply by not slurring throughout this passage. Always question the markings on a score!

Thought Spots: Agustín Barrios’s Saudade from “La Catedral”

“La Catedral,” arguably Agustín Barrios’s most famous work, was not conceived at once. The second and third movements were written in Uruguay in 1921, reflecting the peace of the Cathedral’s interior and the tumult of the town outside. The Prelude, Saudade, was added in La Habana in 1938. (Different versions conflict as to the true genesis of the work, but these seem to be the most accepted facts.)

Saudade is a word of difficult translation, but it is associated with a feeling of longing, of remembrance. What is in the piece–or what was Barrios remembering–that made him add this first movement to the other two, which were inspired by and written in Uruguay?

Agustín Barrios: La Catedral, mvt. I, mm.1-4

It would make sense to think that this Prelude is somehow related to Uruguay. Is it perhaps a milonga? Eduardo Fernández mentioned the idea to me many years ago, and later made a compelling case for it in a thorough analysis of the work, published in the Italian guitar magazine Il Fronimo.

The 3+3+2 subdivision typical of the milonga is embedded in the right hand pattern. Ring finger plays the high notes, and thumb (the strongest finger, carrying an accent) starts the second group of three. Since the campanella effect makes the right hand pattern not to coincide with the arppeggio’s contour, the 3+3+2 subdivision is not evident in most interpretations. Some performers maintain the lowest voices unaccented; others aim to create a dialog between the first and third strings, sort of an echo effect. In fact the thumb notes (the tenor voice in the first four bars) are usually the softest sounding ones. Without labeling any of the interpretations right or wrong, I however encourage you to consider this Saudade as a milonga, and thus place a slight volume or agogic accent on the fourth sixteenth of each measure.

Thought Spots: Manuel Ponce’s “Sonata III”

Here is a spot that can provide for a lengthy discussion:

Manuel Ponce: Sonata III, first movement, mm. 47-50

Let us focus on the first beat of measure 48 (second bar of the example). The open E appears slurred to the following A. This suggests that both notes belong to the same phrase. I would instead consider the following interpretation: the E is the resolution to the line Db-D of the previous bar, and a new phrase begins with the A (second eighth of the bar). In support of this interpretation, notice that the downbeat chord (Fmaj7) does sound as resolution to the previous harmonic progression, the descending leap of fourth of the new phrase (A-E) derives directly from the theme, and this head of phrase is echoed–without a downbeat note–at measure 50. If we agree with this view, then we should not slur the downbeat E to the A, but actually play them slightly detached in order to suggest the end of a phrase and the beginning of another. One would think that the slur is more likely a technical one by Segovia than a musical one by Ponce. What do you think?

Regardless of our interpretation, the example illustrates how we should not blindly follow all the editorial markings on a score, but rather inquire why they are there.

Tempo do Brasil

Congratulations to Marc Regnier on his new album, “Tempo do Brazil,” on Reference Recordings. Marco participated in Sergio Assad’s “Três Cenas Brasileiras ” and wrote the liner notes. Just released! Order here.

New CD by Sebastián Caldas

Congratulations to Uruguayan guitarist Sebastián Caldas on the release of his Tango/Candombe album “Nowruz.” Liner notes by Marco. Order here.